Swiss scientists cut waste and sugar

Imogen Foulkes

Imogen FoulkesImagine picking a nice juicy apple – but instead of biting into it you keep the seed and throw away the rest.

That’s what chocolate manufacturers tend to do with the cocoa bean – they use the beans and throw away the rest.

But now food scientists in Switzerland have come up with a way to make chocolate using the entire cacao fruit instead of just the bean – and without using sugar.

Chocolate, developed at the prestigious Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich by scientist Kim Mishra and his team includes cocoa fruit pulp, juice, and husk, or endocarp.

This program has attracted the attention of sustainable food companies.

They say traditional chocolate production, using only beans, involves leaving some cocoa beans – the size of a pumpkin and packed with nutritional value – to rot in the fields.

The key to fresh chocolate lies in its very sweet, flavorful juice, explains Mr Mishra, “very sweet, like pineapple”.

This juice, which is 14% sugar, is ground down to make a very concentrated syrup, mixed with the pulp and then, taking sustainability to new levels, mixed with the dried husk, or endocarp, to make a delicious cocoa gel.

Gel, when added to cocoa beans to make chocolate, eliminates the need for sugar.

Mr Mishra sees his invention as the latest in a long line of innovations by Swiss chocolate makers.

In the 19th century, Rudolf Lindt, of the famous Lindt chocolate family, accidentally invented the important step of “grinding” chocolate – rolling a mass of warm cocoa to smooth it and reduce its acidity – by leaving the cocoa mass mixture to work overnight. Morning result? Sweet, smooth chocolate.

Lindt

Lindt“You have to be innovative to maintain your product category,” says Mr Mishra. “Or… you’ll make regular chocolate.”

Mr Mishra was partnered in his project by KOA, a Swiss start-up working on sustainable cocoa farming. Its founder, Anian Schreiber, believes that using the entire cacao fruit can solve many of the cacao industry’s problems, from the rising prices of cacao beans to the poverty that exists among cacao farmers.

“‘Instead of fighting over who gets how much of the cake, you make the cake bigger and make everyone benefit,'” he explained.

“Farmers get more money by using cocoa pulp, but also important industrial processing takes place in the country of origin. Creating jobs, creating value that can be distributed in the country of origin.”

Mr Schreiber describes the traditional chocolate production system, where farmers in Africa or South America sell their cocoa beans to large chocolate manufacturers based in rich countries as “unsustainable”.

Imogen Foulkes

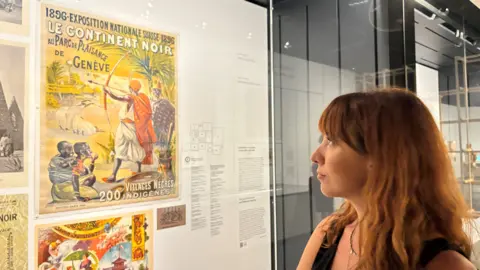

Imogen FoulkesThis image is also being questioned by a new exhibition in Geneva, which explores Switzerland’s colonial history.

For those who point out that Switzerland never had its own colonies, the chocolate historian Letizia Pinoja argues that the Swiss soldiers managed the colonies of other countries, and the Swiss ship owners transported slaves.

Geneva in particular, he says, has some connections to some of the most exploitative sectors of the chocolate industry.

“Geneva is a trading center for goods, and since the 18th century, cocoa has reached Geneva and then all over Switzerland to produce chocolate.

“Without this trade in colonial goods, Switzerland would not be the country of chocolate. And cocoa is no different from any other good form of colonies. They all came from slavery.”

Today, the chocolate industry is highly regulated. Manufacturers must monitor their entire supply chain to ensure that there is no child labor. Also, starting next year, all chocolate imported into the European Union must ensure that no deforestation has taken place to grow the cacao used in it.

But does that mean all problems are solved? Roger Wehrli, the director of the association of Swiss chocolate producers, Chocosuisse, says that there are still cases of child labor and deforestation, especially in Africa. He fears that some manufacturers, in an attempt to avoid the challenges, simply shift their production to South America.

“Does this solve the problem in Africa? No. I think it would be better for honest firms to stay in Africa and help improve the situation.”

That’s why Mr. Wehrli sees the new chocolate made in Zurich as “very promising… If you use the whole cacao fruit, you can get better prices. So it’s economically interesting for farmers. And it’s interesting from an environmental point of view. .”

Chocosuisse

ChocosuisseThe connection between chocolate production and the environment is also emphasized by Anian Schreiber. A third of all farm produce, he says, “doesn’t end up in our mouths”.

Those statistics are even worse for cocoa, if the fruit is left to use only the bean. “It’s like throwing away an apple and using its seeds. That’s what we’re doing right now with the cacao fruit.”

Food production involves the release of greenhouse gases, so reducing food pollution may help tackle climate change. Chocolate, a niche luxury item, it may not be a big deal in itself, but both Mr Schreiber and Mr Wehrli believe it could be a start.

But, back in the laboratory, important questions remain. How much will this new chocolate cost? And, most importantly, without sugar, how does it really taste?

The answer to the last question, in this chocolate-loving writer’s opinion, is: surprisingly good. A rich, dark but sweet flavor, with a hint of cocoa that would go well with an after-dinner coffee.

Costs may remain a challenge, given the global power of the sugar industry, and the many subsidies it receives. “The cheapest ingredient in food will always be sugar as long as we subsidize it,” explains Kim Mishra. “With… a tonne of sugar, you pay $US500 [£394] or less.” Cocoa pulp and juice cost more, so fresh chocolate, meanwhile, will be more expensive.

Still, chocolate producers in cacao-growing countries, from Hawaii to Guatemala to Ghana, have contacted Mr. Mishra for information about the new method.

Chocosuisse

ChocosuisseIn Switzerland, some of the biggest manufacturers – including Lindt – are starting to use cocoa beans and beans, but no one, so far, has taken the step to completely eliminate sugar.

“We have to find brave chocolate manufacturers who want to explore the market and are willing to contribute to sustainable chocolate,” said Mr Mishra. “Then we can disrupt the system.”

Perhaps those bravest producers will be found in Switzerland, whose chocolate industry makes 200,000 tonnes of chocolate each year, worth around $US2bn. At Chocosuisse, Roger Wehrli sees a stable, but bright future.

“I think chocolate will still taste good in the future,” he insisted. “And I think the demand will increase in the future because of the increase in the population of the world.”

And will they eat Swiss chocolate? “Obviously,” he said.

Source link