Kohler’s unconventional tactic to encourage innovation: let artists run the industry

Artist David Franklin was sitting on a tree stump in rural Washington when he answered the phone call that would change his life.

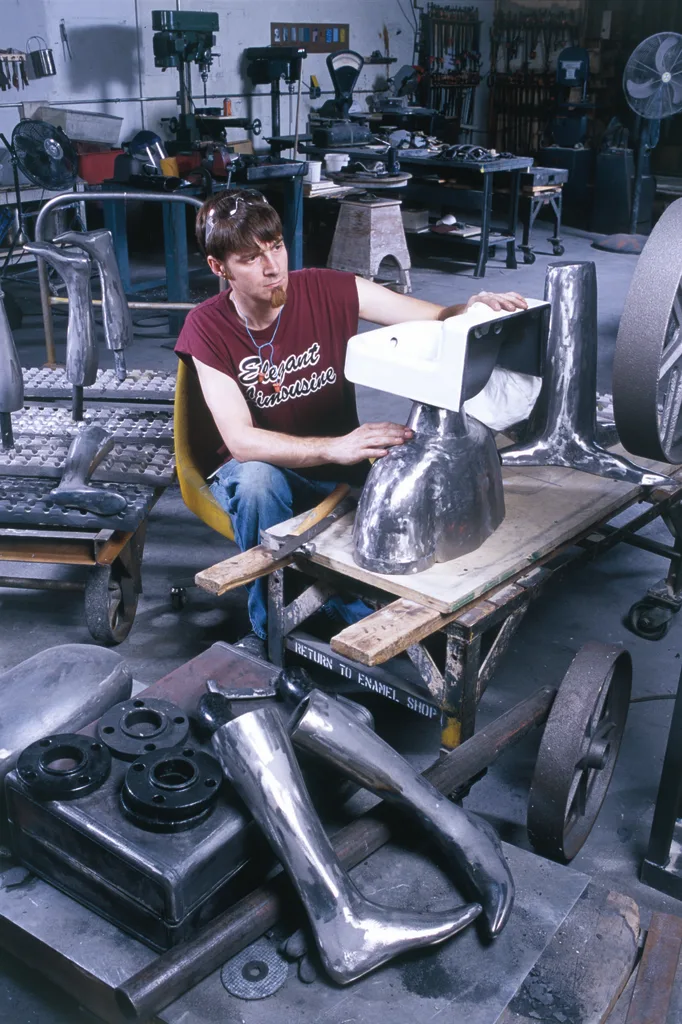

In the early 2010s, Franklin was having difficulty finding creative work, and had taken a position as a lumberjack, taking measurements in remote areas of trees for a forestry company. He had also applied for a job at the factory. But it was no ordinary production job. It was a special residency program that placed twelve artists each year at the Kohler Company’s Wisconsin manufacturing facilities, where they created art with the same clay or metal tools used by factory workers to make plumbing fixtures.

While at the forest workshop, Franklin found a place with cell phone reception and a stump to sit on to talk on the phone which helped him win a seat in the session. Like other artists who have gone through the residency, he found the experience life-changing, exposing him to new tools and practices beyond the wood carving techniques he was most familiar with. It also opened the door for years of public art commissions, said Franklin, who will have a large piece on display at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium.

“It was really cool,” he says. “I love working and making things with my hands, and then I was in this big world of art that I’ve never seen before, and that was amazing.”

The Arts/Industry program is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. A partnership between the family-owned Kohler Company and the John Michael Kohler Arts Center museum in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, today offers artists three months of unique access to industrial equipment, materials, technical assistance, housing, and a small fee. It also provides inspiration and ideas to Kohler craftsmen and designers, influencing the look of other Kohler faucets such as the company’s Artist Editions line.

Even though art residencies have proliferated, Kohler’s residency remains a rare opportunity. So much so, that the latest application round attracted more than 600 applicants for 12 annual positions—six in creativity, six in ceramics—making it an Ivy League university.

“The Kohler residence is one of the most unique residences in the world,” said artist Beth Lipman, who participated in both the pottery and design residencies and served as the program’s coordinator for nearly five years. “There is none [another] consistent stay, long stay anyone can apply to work in a factory to make art in this way. “

The industry is alive

The program began after a 1973 contemporary ceramics exhibition at the Arts Center titled “The Plastic Earth.” At that time, says Art Center Executive Director Amy Horst, the art world was sharply divided between craft and fine art. But Ruth DeYoung Kohler II, who then headed the Art Center, brought artists with work in the exhibit to tour the Kohler factory, where they were fascinated by the ceramic work being done. He soon invited artists Jack Earl and Tom Ladousa to spend a month working as potters at the factory, then expanded the residency program with the help of his brother Herbert V. Kohler Jr., who then headed the Kohler Company.

“He said, ‘Ruthie, I have a factory, you have artists, let’s see if this will work,'” said Laura Kohler, CEO of the organic company and daughter of Herbert Kohler.

At the time, most artists had not spent much time in factories, and many of the Kohler factory workers did not have much experience in the art world. But the artists were soon impressed by the workers’ level of professionalism and deep expertise, and factory workers appreciated the artists’ willingness to work long hours to master new techniques and do as much as possible with their limited time in the building. Horst says: “The mutual respect that was established and the strength that exists between them is what strengthened this program for 50 years.

Franklin, for example, found himself interacting with factory workers in the process of turning wooden sculptures into molds for schools of clay fish, a natural conversation starter at a workplace just a few minutes’ drive from Lake Michigan. He says: “The fish thing suddenly became popular with people. “The fishing culture around the Great Lakes is huge.”

Hard hat seating

The residency does not require applicants to have experience in pottery or metalwork, and many artists have backgrounds in other fields. That can make for a steep but rewarding learning curve as artists wear hard hats and safety glasses and learn to use new tools to produce work on an industrial scale. Residents are expected to leave one part with the Kohler Company and one with the Arts Center, but both jobs may end up being a small part of what they create. “Everybody is attracted to the opportunity to do something incredibly versatile, so even non-doers quickly become doers within that space,” says Horst.

Both potters and founders have a specialist dedicated to helping artists, and factory workers often weigh in with tips and troubleshooting advice about, say, making molds, but artists are generally expected to quickly adapt to the heat, noise, physical labor, and safety procedures found in factory work.

“It can be physically demanding, but it’s very rewarding,” said conceptual artist Edra Soto, who is currently doing a second residency at the clay studio. “To be removed from my daily life in the studio with the help of technology is like a dream come true for a musician like me.”

Soto, a Puerto Rican-born artist now based in Chicago, has used the space for various projects. Another turns recycled cognac bottles found in his neighborhood into works of art. Others include colorful clay theater masks and colorful tiles inspired by Puerto Rican architecture. “It’s three months, but it goes by fast, so one thing I’ve been thinking about a lot is to choose a few projects that I can focus on and expand on,” he said.

Some artists have found ways to work with forms already produced by the Kohler factory. Willie Cole, a New Jersey artist who had a pottery show in 2000 and now has an exhibit at the Arts Center, says that at the time he worked mostly with found objects, so some of his work at the Kohler factory included animal sculptures. from bits of ceramic and hardware extracted from incomplete materials that would otherwise have been discarded. “I like to automate, so I had all these pieces on the table, but it wasn’t something I was working on all day,” he said. “It was something I went through day after day, and I moved a small piece like a jigsaw puzzle.”

Once they’ve mastered what’s available, artists sometimes return to residences to expand on their work or try new techniques. While living in the original location for several years after his work at the museum, Lipman created a series of metal works entitled. Distill, made of cardboard dioramas holding miniature furniture and “ancient plants” such as lichen and ferns. He credits his time working on the residential system with giving him the knowledge to take the project as far as he could, such as adding chrome, enamel, and rust patina to the works.

He says: “I saw a lot of residents who were building houses passing by.” “I was able to put together the information as if I had that position, but it was because of seeing their process a little bit.”

Art as an important part of business

Kohler centers often blur the lines between art and industrial design. Artists, including former residents, designed stunning public toilets for the Arts Center’s main building and its Art Preserve, which houses the archive and showcases spaces such as artists’ homes and workspaces. The toilets—the museum’s preferred term—are themselves works of art that are almost intimidating to use for their intended purpose, including one designed by Lipman tiled with ceramic images of local plant specimens from the University of Wisconsin. And the installation based on the Kohler factory studios, on display at the Arts Center as part of the 50th anniversary celebration, feels like a cousin to the artist spaces on display at the Preserve.

The work produced at the Kohler residence is often displayed in the company’s showrooms around the world and, with weatherproof pieces, alongside the outdoor art walk near the company’s headquarters. The company bought one of Franklin’s fish pieces and placed it in its Kohler Experience Center in West Hollywood, helping win more commissions from homeowners who were impressed by his style, he says.

“Our philosophy with Arts/Industry is to showcase the work,” Laura Kohler said. “Don’t keep the work, but get it out and let people hear it.”

Over the years, craftsmanship based on plumbing fixtures has influenced Kohler’s designs. The Artist Editions line appeared in 1981 after resident potter Jan Axel created a sink design that caught the Kohlers’ eye. “We liked it so much, we wanted to do it commercially,” said Laura Kohler. “I think my dad probably saw it and said, ‘I want to see if I can do that at a high level.'”

Artists over the years have continued to put Kohler manufacturing technology to new uses. After artists recently inquired about the 3D printer used in the factory, the company purchased a second one for their use. Soto recently used it to help produce enlarged versions of his masks. The new “MakerSpace” program brings artists by special invitation—it’s where Franklin created his new work for the Shedd, as well as a new set of fish for the Kohler Experience Center in Miami, and artist Patty Chang will soon work there on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Some artists have recently worked with materials from Kohler’s WasteLAB, where the company in recent years has designed ways to use scraps that would otherwise go to landfills. And to finish off some of his fish, Franklin and other factory workers experimented with physical vapor deposition (PVD), a process previously used at the factory only to deposit shiny materials on metal bases such as faucets, instead of ceramics.

Laura Kohler says: “That’s the kind of discovery that happens with this partnership.”

Source link