Firing Pat Gelsinger does not solve Intel’s problems

Despite Intel’s recent woes, I didn’t expect to see . Gelsinger is a stable engineer and business success who laid down a comprehensive rescue plan when he took the leadership of the stricken chip maker in 2021. It wouldn’t be a quick fix, given the company’s long legacy of missteps. Gelsinger may be the public face of Intel’s current malaise, but the problems started before his time and will likely continue.

How Intel got here

Gelsinger has been tasked with dealing with nearly two decades of bad decisions, all of which have been compounded. Intel became a behemoth that engulfed the industry as one unit, producing chips that went hand in hand with Microsoft Windows. The huge profits that came from these relationships meant that there was an institutional reluctance to look too hard at new businesses that might interfere with their success, which continues to be strong all these years later.

In 2005, former CEO Paul Ottellini developed the iPhone’s system-on-chip. It would be easy for Intel, because it already makes XScale ARM chips for mobile devices. You can find the Intel ARM chip inside popular phones like the BlackBerry Pearl 8100 and the Palm Treo 650. A year later, it will sell XScale to Marvell, believing it will be able to scale down its x86 chips to run on smartphones. It is, but the Snapdragons of the day – produced by much smaller rival Qualcomm – beat them easily.

At the same time, Intel was working on Larrabee, its own dedicated GPU platform based on the x86 architecture. Despite several years of marketing bravado and hints that it will, Intel. This decision will give NVIDIA the bulk of the GPU market, making it a name for games, supercomputers, crypto and AI, posting quarterly earnings on November 20.

Did Intel foresee the meteoric rise of AI? Maybe not. But former Intel CEO Bob Swan reportedly turned down an opportunity to invest in OpenAI in 2017. It was looking for a hardware partner to reduce its reliance on NVIDIA, offering an open deal in the process. Swan, however, reportedly said he doesn’t see a future for AI in production, and Intel’s data center unit refuses to sell hardware at a discount.

Intel’s core strength was in the quality of its engineering, the durability of its product and that it was always close to the cutting edge. (There are parallels to be drawn between Intel and Boeing, both of which are watching their reputations erode in real time.) Sadly Intel’s bread-and-butter business took a nosedive after the company failed to produce 10-nanometer chips by the planned 2015 deadline. The company’s famous “tick, tock” strategy of introducing a new chip process one year and a refined version the next will stop.

These problems enabled Intel’s competitors to step in and steal the march, using modern chip architectures. AMD, which has been holding back for much of the 2010s, has seen its file . The biggest beneficiary of all, was TSMC, the Taiwanese chip factory that has become the envy of the world. Although Intel controls the majority of the x86 processor market, it is TSMC that makes chips for Apple, Qualcomm, NVIDIA and AMD, among others. Intel, on the other hand, was tied to an old chip manufacturing process that it could not use to catch up with its competitors.

The Gelsinger Doctrine

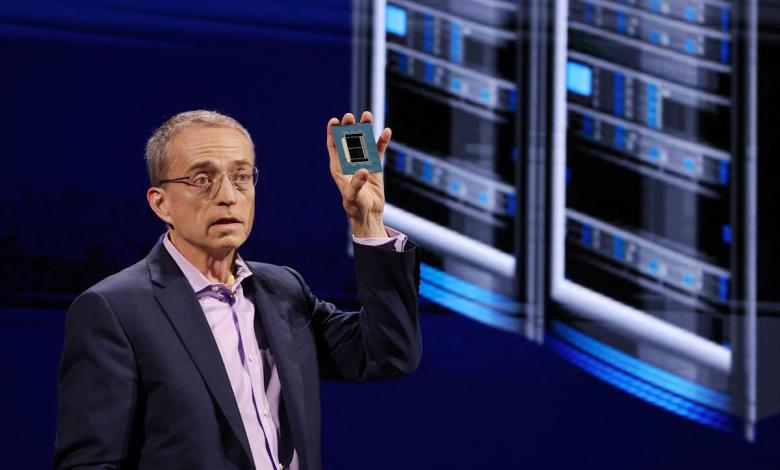

Gelsinger was as close to an Intel “lifer” as you can imagine, joining the company at age 18 and rising to the position of Chief Technology Officer in 2001. In 2009, he left Intel to become COO at EMC and held the position of CEO at VMWare for nearly ten years. After taking over Intel, he laid out a detailed plan to orchestrate its glorious comeback.

The first step would be to split Intel’s design and manufacturing business into . With one eye on Biden’s CHIPS and Science Act, Gelsinger has promised to build two chip factories using the same EUV (Extreme Ultraviolet Lithography) technology used by TSMC.

Gelsinger also set out to restore discipline in Intel’s chip business and return to the “tick, tock” structure. Unfortunately, production delays that have been increasing since 2015 meant that Gelsinger’s goal was to return to parity. In the meantime, Intel will also get TSMC to make some of its new chips, which, while expensive, will help address any concerns the company was lagging behind.

No one doubted the enormity of the task facing Gelsinger, but there was plenty of room for optimism. Gelsinger was humble enough to accept that Intel could not simply stay on its current path, and had to accept its new status. He suggested that Intel could grin and bear the temporary pain so that the company could benefit in the long run. If it could build for the future, tie up its competitors to keep it in the game and restore faith in its processes, Intel will come out victorious. It just needed to make it worse.

Things got worse

At the end of October, reported that Gelsinger made a major faux-pas when talking about TSMC. The Chief Executive was quoted as saying “You don’t want all our eggs in the Taiwan cloth basket,” and that “Taiwan is not a stable place.” This so angered TSMC that it ended the rebate that Intel had used for years

Sadly, Gelsinger’s desire to restore discipline to the chip division will backfire, as the latest Core processors are plagued by the . Intel was forced to , which came at an additional cost that it could not afford. In August, it posted a loss. But it was forced three months later, to lose $16.6 billion, though much of that was related to analyzing the company’s assets and paying for layoffs. Even worse, Intel’s new manufacturing process, 18A, is reportedly .

Perhaps the lowest point in Intel’s year was when its stock price fell enough that it became a takeover target. Rumors while others show .

Where does this leave Intel?

reports Intel’s board is frustrated with Gelsinger as his rescue plan “wasn’t showing results fast enough.” But Intel wouldn’t hire Gelsinger in 2021 and suddenly back in 2024. Building large and complex chip factories is not easy. And getting thousands of engineers to solve difficult problems about chip yield. And clearly reversing the slide that began in 2015 was not going to happen overnight.

Intel’s board is currently looking for a full-time replacement for Gelsinger but it’s hard to see what anyone else will do differently. After all, the company still needs to build those factories to own and control its future, it still needs to adjust its processes. Unless, of course, the next CEO is told to just stop the bleeding and keep the money rolling in. Even though it is in its most damaged state after a few bad places, Intel is still the biggest name in the x86 chip world again. you will continue to make money for years to come.

You can easily imagine Intel’s board sitting around, putting forward a few years of healthy profits at the expense of the company’s long-term future. It can continue to sell modified versions of its existing desktop chips, leaving the technology leadership to AMD, Qualcomm and others. For about a decade or two large industrial clients were happy to use Intel processors for their hardware as long as they still ran Windows. Perhaps that will be appropriate given how big and ossified Intel has become, admitting it can’t move fast enough to evolve.

It is likely that the situation will not be allowed to happen given Intel’s extensive role in the world’s technology scene. Even if the incoming administration criticizes the CHIPS Act — Intel is still set to own one — having a domestic manufacturer of Intel’s scale will be an asset few smart governments would let fall. But just changing CEOs won’t fix the company’s big, hard-to-solve problems. It wasn’t Pat Gelsinger who designed the power design of Raptor Lake, and he didn’t give a chance to make the iPhone CPU all those years ago. TSMC stuff, he can own that, but while the CEO sets the direction, he can’t control the entire process in a company of Intel’s scale. So whoever replaces him will have a lot of problems to deal with, knowing that the board’s patience will be very short this time.

Source link