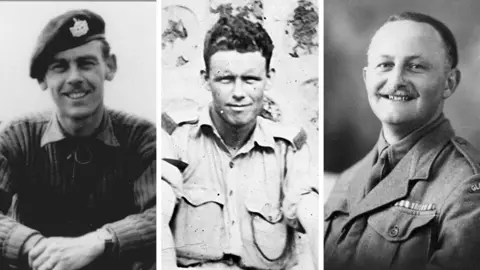

Families reunited with the bodies of missing British soldiers

BBC

BBCFrom his wheelchair, Michael Northey looks silently at his father’s grave, and lays a flower for the first time.

“This is the closest I’ve been to him in 70 years, which is funny,” he joked bitterly.

Born into a poor family in the back streets of Portsmouth, Michael was still a child when his father, the youngest of 13 children, left to fight in the Korean War. He was killed in action and his body has never been found.

For decades, it lay in an unmarked grave at the UN cemetery in Busan, on the southern coast of Korea, adorned with a plaque reading ‘A member of the British Army, known to God’.

It now bears his name – Sergeant D. Northey, died 24th April 1951, aged 23.

Sergeant Northey, along with three others, are the first unidentified British soldiers killed in the Korean War to be successfully identified, and Michael attended the ceremony, along with other families, to rename their graves.

Michael had spent years doing his own research, hoping to find out where his father was, but eventually gave up.

“I’m sick and I don’t have much time left for myself, so I was putting it off, I thought I wouldn’t be able to,” he said.

But a few months ago, Michael got a call. Unbeknownst to him, Department of Defense researchers were conducting their own investigation. When he heard this news, he said “he cried for 20 minutes”.

“I can’t describe the emotional release,” he said with a smile. “This has troubled me for 70 years. I sympathized with the lady who called me.”

The woman on the other end of the phone was Nicola Nash, a forensic researcher from the Joint Casualty and Compassionate Center in Gloucester, which routinely works to identify victims of the First and Second World Wars.

Commissioned for the first time to find the dead of the Korean War, he had to start over by compiling a list of the 300 missing British soldiers, 76 of whom were buried in Busan Cemetery.

Nicola passed on their burial reports, and found only one man buried wearing stripes was a sergeant from the Gloucester Regiment, and one grandfather.

After combing national archives and referencing eyewitness accounts, family letters and military office reports, Ms Nash was able to identify the men as Sergeant Northey and Major Patrick Angier.

Both were killed in the famous Battle of the Imjin River in April 1951, as the Chinese Army, which had joined the war on the side of North Korea, tried to push the allied forces on the peninsula to take the capital Seoul. Despite being outnumbered, the men held their position for three days, giving their colleagues enough time to retreat and successfully defend the city.

The issue at that time, explained Ms. Nash, was that because the war was bloody, most of the men were killed or captured, and no one was left behind. The enemy had removed and distributed their dog tags. It wasn’t until the prisoners of war were released that they could share their accounts, and no one had thought to go back and reconcile these issues – until now.

For Ms Nash, this has been a six-year “labor of love”, made easy, she admits that some of the men’s children are still alive to paint, which has made the project all the more important.

“The children have spent their whole lives not knowing what happened to their father, and the fact that I am able to do this work and bring them here to their graves, say goodbye and close that says it all,” he said.

In this event, families sit in chairs between long rows of small stone graves, marking the thousands of foreign soldiers who fought and died in the Korean War. They were accompanied by soldiers serving in the old formations of their loved ones.

Major Angier’s daughter, Tabby, now 77, and his grandson, Guy, stopped by to read excerpts from his best-selling books. In one of his last speeches, he tells his wife: “We love our beloved children very much. Tell them how much my father misses them and he will come back when he finishes his work”.

Tabby was three years old when his father went to war, and his memories of him are broken. He says: “I remember someone standing in the room piling canvas bags, which were probably the things he was going to use to go to Korea, but I can’t see his face.

At the time of her father’s death, people didn’t like to talk about wars, Tabby said. Instead, those in his Gloucestershire village used to comment: “Oh, those poor children, they’ve lost their father.”

“I used to think that if he was lost, they would find him,” said Tabby.

But as the years passed and she learned what had happened, Tabby was told that her father’s body would never be found. The last recorded clue was that it was left under an overturned boat on the battlefield.

Tabby has visited this cemetery twice before, trying to get as close to her father as she could imagine, not knowing that he was here all this time. “I think it’s going to take a while to sink in,” she said, from her newly decorated grave.

The shock was great for 25-year-old Cameron Adair from Scunthorpe, whose great uncle, Corporal William Adair, is one of two Royal Ulster Rifles soldiers Ms Nash was also able to identify. Another is Rifleman Mark Foster from County Durham.

Both men were killed in January 1951 when they were forced to repel a wave of Chinese troops. Corporal Adair never had children, and when his wife died so did his memory, leaving Cameron and his family unaware of his existence.

Finding a relative who “helped bring freedom to a lot of people” made Cameron “really proud,” he said. “Coming here and witnessing this has really brought us home”.

Now that he is the same age as his uncle when he was killed, Cameron feels inspired and says he would like to serve if the need arises.

Ms Nash is now collecting DNA samples from relatives of another 300 missing soldiers, in the hope that she can give more families the same peace and happiness that she brought Cameron, Tabby and Michael.

“If there are still missing British workers, we will continue to try to find them,” he said.

Source link