Cubans endure days without power as the energy crisis hits hard

BBC

BBCCuba has endured one of the toughest weeks in years after a nationwide blackout left around 10 million Cubans without power for several days. Adding to the Caribbean island’s woes, Hurricane Oscar left a trail of destruction along the northeast coast, leaving several dead and causing extensive damage. In some Cuban communities the energy crisis is the new normal.

As Cuba approaches its fourth day without power this week, Yusely Perez turned to the only source of fuel he had left: firewood.

His neighborhood in Havana has not received regular deliveries of canned gas for two months. So when the entire island’s electricity went down, causing a nationwide blackout, Yusely was forced to take drastic measures.

“My husband and I went all over town, but we didn’t find coal,” she explains.

“We had to collect firewood wherever we found it on the road. I’m thankful it’s dry enough to cook with.”

Yusely nodded at the yucca chips that were slowly frying in a pot of warm oil. He adds: “We have been without food for two days.

AFP

AFPSpeaking last Sunday, at the height of the worst electricity situation in Cuba in years, the minister of energy and mines in that country, Vicente de la O Levy, blamed the problems of the deterioration of the electricity infrastructure on what he called the “cruel” US economy. prohibition in Cuba.

The ban, he said, made it impossible to import new parts to rebuild the grid or bring in enough fuel to run power stations, or even access credit from the international banking system.

The US State Department responded that Cuba’s energy production problems were not Washington’s fault – but argued that it was due to the Cuban government’s mismanagement.

Regular service will resume soon, the Cuban minister emphasized. But before he could say those words, the grid collapsed, for the fourth time in 48 hours.

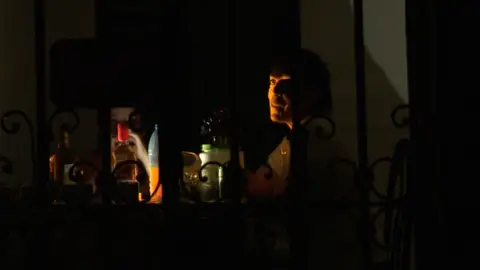

At night, it was clear that the electricity had been cut off.

The streets of Havana were plunged into pitch blackness as residents sat outside in the sweltering heat, their faces illuminated by cellphones – as long as their batteries still lasted.

Others, like restaurant worker Victor, were ready to openly criticize the authorities.

“The people who run this country don’t have all the answers,” he said. “But they will have to explain themselves to the Cuban people.”

In particular, the government’s decision to invest heavily in tourism, rather than energy infrastructure, frustrated him greatly during the blackout.

“They have built too many hotels in the last few years. Everyone knows that a hotel doesn’t cost a few bucks. It costs $300 or $400 million.”

“So why is our energy infrastructure collapsing?” he asks. “Either they don’t invest in it or, if they invest, it doesn’t help the people.”

Aware of the growing discontent, President Miguel Diaz-Canel appeared on state television wearing the traditional olive green fatigues of the Cuban revolution.

If that message isn’t clear enough, he specifically warned people to protest the blackout. Authorities will not “tolerate” vandalism, he said, or any attempt to “disrupt public order”.

AFP

AFPI protests in July 2021, when hundreds were arrested amid widespread protests following a series of blackouts, they were recently recalled.

At this event, there were only a few reports of isolated incidents.

However, the question of where Cuba chooses to direct its scarce resources remains controversial on the island.

“When we talk about energy infrastructure, that refers to both generation and distribution or transmission. At every step, a lot of investment is needed,” said Cuban economist Ricardo Torres at the American University in Washington DC.

Electricity generation in Cuba has recently fallen far below what is needed, providing only 60-70 percent of national demand. The shortage is a “big and bad gap” that is now being felt across the island, Mr Torres said.

According to the government’s own statistics, the national electricity generation in Cuba will decrease by about 2.5% in 2023 compared to the previous year, which is part of the 25% decrease in production from 2019.

“It is important to understand that last week’s problem in the electricity grid is not something that happened overnight,” said Mr. Torres.

Few know that better than Marbeyis Aguilera. The 28-year-old mother of three is used to living without electricity.

For Marbeyis, even a “regular service” restoration still means most of the day without power.

In fact, what the residents of Havana will endure for a few days is similar to daily life in their village of Aguacate in the province of Artemisa, outside of Havana.

“We have been without power for six days”, he said as he brewed coffee on a makeshift charcoal stove inside his shack with a tin roof.

“It went in for a few hours last night and then went out again. We have no choice but to cook in this way or use wood to give the children something warm,” he added.

His two electric starters and an electric ring sat idle on the kitchen floor, the room filled with smoke. The community is in dire need of government assistance, he said, listing the priorities that are most important to them.

“First, electricity. Second, we need water. Food is running out. People with dollars, sent from abroad, can buy food. But we don’t have it, so we won’t buy anything.”

Marbeyis says some of the biggest problems in Aguacate – food insecurity and water distribution – have been exacerbated by the power cuts.

Her husband’s manual work also requires electricity and she is stuck at home waiting for orders to come to work. The Cuban government was supposed to bring back state workers on Thursday – but to avoid another collapse in the grid, all non-essential activities and schools are now suspended until next week.

“It’s especially difficult for children”, Marbeyis adds, his eyes full of tears, “because if they say I want this or that, we have nothing to give them.”

Living without a reliable power source is the new normal in places like Aguacate. Many have been struggling with power shortages since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has accompanied the island’s deep economic downturn.

Perhaps the biggest problem of the Cuban Empire is that seeing people cooking with wood and charcoal in the 21st century reminds us of poverty under the dictatorship of Fulgencio Bastista, who was overthrown by revolutionaries six and a half decades ago.

In the midst of it all, on the northeast coast, the situation worsened. As people were still dealing with power outages, Hurricane Oscar made landfall, bringing strong winds, flooding and tearing roofs off homes.

The storm may have passed. But Cubans know that such is the critical state of the island’s energy infrastructure that the next blackout across the country could happen at any time.

Source link