Moscow and Putin are wary of Donald Trump’s second term

BBC

BBCYour advice – never buy a large amount of champagne unless you are sure it is worth celebrating.

In November 2016, the Russian ultranationalist politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky was very happy with the victory of Donald Trump, and convinced that it will change US-Russian relations, he exploded 132 bottles in the Duma, the Russian parliament, and broke up (in his party offices) in front of the television cameras.

He wasn’t the only one celebrating.

The day after Trump’s surprise White House win, Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of the state channel RT, tweeted her intention to drive to Moscow with an American flag on her car window.

And I’ll never forget the time a Russian official told me we smoked a cigar and drank a bottle of champagne (yes, MORE champagne) to toast Trump’s win.

In Moscow, it was expected that Trump would lift the sanctions against Russia; perhaps, even, consider the Crimean Peninsula, which is annexed to Ukraine, as part of Russia.

“Trump’s importance was that he never preached about human rights in Russia,” explained Konstantin Remchukov, the owner and editor-in-chief of the Nezavisimaya Gazeta newspaper.

It didn’t take long for all that fizz to go away.

“Trump introduced the toughest sanctions against Russia at that time,” Remchukov recalled.

“At the end of his term, a lot of people were disappointed with him being president.”

That’s why, eight years on – at least publicly – Russian officials are very cautious about the prospect of a second term for Trump.

President Vladimir Putin even came out and endorsed the Democratic Party candidate, although that “endorsement” was widely interpreted as a Kremlin joke (or Kremlin trolling).

Putin said he liked Kamala Harris’ “infectious” laugh.

But you don’t need to be a seasoned political scientist to understand that on the campaign trail it was Trump, not Harris, who was guaranteed to put a smile on Putin’s face.

For example, Trump’s criticism of the level of US military aid to Ukraine, his apparent reluctance to blame Putin for a full-scale attack on Russia and, during a presidential debate, his refusal to say whether he wants Ukraine to win the war.

In contrast, Kamala Harris said that support for Ukraine is in the “strategic hands” of America and called Putin a “deadly dictator”.

Not that Russian national TV was praising him too much either. A few weeks ago one of Russia’s most famous news anchors knew that Harris had political skills. He suggested that he would be better off hosting a TV cooking show.

There is another possible outcome for the Kremlin – a tight election, followed by a disputed result. An America consumed by post-election chaos, confusion and confrontation would have had little time to focus on foreign affairs, including the war in Ukraine.

US-Russian relations that deteriorated under Barack Obama, worsened under Donald Trump and, according to the recently departed Russian ambassador to Washington Anatoly Antonov, are “falling apart” under Joe Biden.

Washington puts the blame squarely on Moscow.

It was just eight months after Putin and Biden met at a conference in Geneva when the Kremlin leader ordered Russia to attack Ukraine in full.

Not only has the Biden administration sent a tsunami of sanctions Russia’s way, but US military aid has been crucial in helping Kyiv survive more than two and a half years of Russian war. Among the advanced weapons that the United States has provided to Ukraine are Abrams tanks and HIMARS rockets.

It is hard to believe now that there was a time, not so long ago, when Russia and the US were committed to working together as partners to strengthen global security.

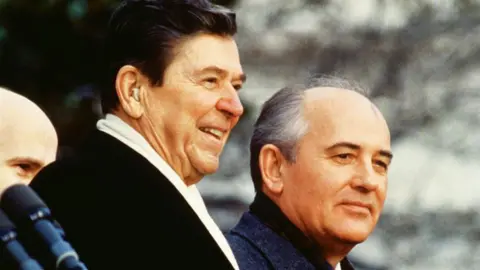

In the late 1980s Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev created a geo-political double-act to destroy their countries’ nuclear weapons.

If there was one thing Reagan seemed to enjoy like denuclearization he was repeating Russian proverbs to Gorbachev in broken Russian (“Never buy 132 bottles of champagne unless you’re sure it’s worth celebrating” would be great).

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1991 the First Ladies of the USSR and America, Raisa Gorbacheva and Barbara Bush, unveiled an unusual monument in Moscow – a mother duck with eight ducklings.

It was a sculpture in the Boston Public Gardens and was presented in Moscow as a symbol of friendship between Soviet and American children.

It is still popular among Muscovites today. Russians flock to Novodevichy Park to take photos with the bronze birds, although few visitors know the back story of the superpower’s “duck diplomacy”.

Like the US-Russian relationship itself, the ducks have taken a few knocks. At some point some of them were stolen and had to be replaced.

I go to the Moscow mallard and its ducks to find out what the Russians think about America and the US election.

“I want America to disappear,” said angry fisherman Igor fishing in a nearby lake. “Many wars have started in the world. The US was our enemy during the Soviet era and still is. It doesn’t matter who the president is.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAmerica as the eternal enemy of Russia – that is the worldview that often appears here in the state media. Is Igor very angry because he gets his news on Russian TV? Or maybe it’s because he hasn’t caught many fish yet.

Most of the people I talk to here do not see America as a bad enemy.

“All I fight for is peace and friendship,” said Svetlana. “But my friend in America is afraid to call me now. Maybe there is no free speech there. Or, perhaps, it is here in Russia that there is no freedom of speech. I don’t know.”

“Our countries and our two peoples should be friends,” said Nikita, “without wars and without competing to see who has more missiles.” I prefer Trump. When he was president, there were no major wars.”

Although there are differences between Russia and America, there is one thing these countries have in common – they always have male presidents.

Will the Russians ever see that change?

“I think it would be good if a woman became president,” said Marina.

“I would be happy to vote for a female president here [in Russia]. I’m not saying it will be better or worse. But it will be different.”

Between now and the US election on 5 November, the BBC’s correspondents in other parts of the world are exploring the impact their results will have where they are, and what people around the world are doing about the race for the White House.

Source link