Two million at risk of starvation in Tigray, aid official warns

Ed Ram/Getty

Ed Ram/GettyA humanitarian crisis is unfolding in northern Ethiopia, driven by drought, crop failure and ongoing insecurity after a brutal war.

As local officials warn that more than two million people are now at risk of starvation, the BBC has gained exclusive access to some of the worst-hit areas in Tigray province, and analyzed satellite images to reveal the full scale of the emergency the region is now facing. .

The month of July is an important time for food availability, when farmers must harvest their crops to take advantage of the annual rainfall.

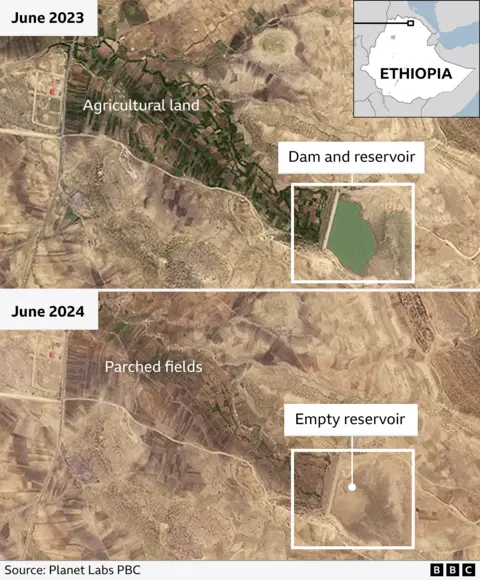

The satellite images that we have identified show that the dams and farms that are helping with irrigation are dry because the rains did not fall last year. Now they need to be filled by the seasonal rains so that farmers can hope for a successful season at the end of the year.

The pictures below are of the Korir dam and dam, about 45 kilometers (28 miles) north of the regional capital, Mekele.

A small reservoir with an artificial barrier, known as a small dam, is clearly visible in the first photo, taken in June 2023. Below the dam is fertile land irrigated by the dam.

Programs like these have been able to support more than 300 farmers who grow wheat, vegetables and millets – grains.

The image below shows the same area in June 2024, with an empty lake and cultivated fields.

Without enough rain, the irrigation system will not work and farmers cannot survive without land.

“Even though our dam has no water, our land will not go anywhere,” said Demtsu Gebremedhin who was growing tomatoes, onions and millet.

“So we are not discouraged and we hope to return to farming.”

Food and security

The population of Tigray is estimated at between six and seven million.

Until the end of 2022, the region was engulfed in a two-year war between the local forces of Tigray and the federal government and its allies.

It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people were killed in the war, or died from starvation and lack of health care.

A number of displacement camps were set up to provide shelter, and humanitarian support.

Ed Ram/Getty

Ed Ram/GettyNow that the war is over, some have been able to return to their homes – but most of them are still in the camps, relying on the delivery of food aid because the lack of rain means they have no crops to harvest and eat.

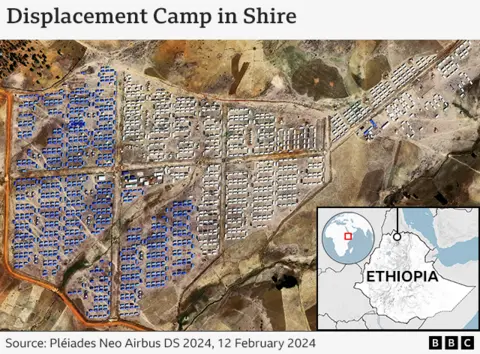

One of these camps is near the town of Shire about 280 kilometers (174 miles) by road to the west of the Korir dam. Established by UN agencies, it now provides shelter to more than 30,000 people.

The green tents seen in this satellite image were provided by the International Organization of Migration (IOM) and the white ones by the UN refugee agency (UNHCR).

Pléiades Neo © Airbus DS 2024

Pléiades Neo © Airbus DS 2024Tsibktey Teklay takes care of her five children in the camp. Her husband was killed in the war.

“We had animals. We used to harvest crops in the winter,” he told the BBC in May. “In short, we were living in the best possible way. Now we are nothing.”

In the camp, she does cooking and manual work to earn money, but some of her children have had to beg.

“I hope that at least I will get my land. Food grown on our land is better than food aid,” he said.

“If we can return to our town, our children can work or go to school.

So I hope that after our hard life here, this will be a better future for them.”

Children facing malnutrition

The BBC spoke to doctors at a hospital in the town of Endabaguna, 20 kilometers south of the Shire about their growing concern.

The medical director of this hospital, Dr. Gebrekristos Gidey says: “We have been treating an increasing number of children in recent months.

Another woman – Abba Yeshalem, 20, gave birth prematurely due to malnutrition, he says.

At the hospital, Abeba told us: “My husband went away to study, he left me alone, and he could not help me financially. I don’t have enough food to cook for myself or the baby.

A large number of children who are treated are not only from families living in the camps, but also those from nearby towns.

“We don’t have the resources to take care of all the needy,” said Dr. Gebrekristos.

Waiting for the rain

The region is facing the most critical time of the year, known as “the season of great hunger” according to Dr. Gebrehiwet Gebregzabher, head of the Tigray Disaster Management Commission.

It’s a time when normal food is running low – and crops must be planted to be ready for the October harvest.

“There are 2.1 million people at risk of starvation,” he told the BBC, “and another 2.4 million dependent on uncertain aid.”

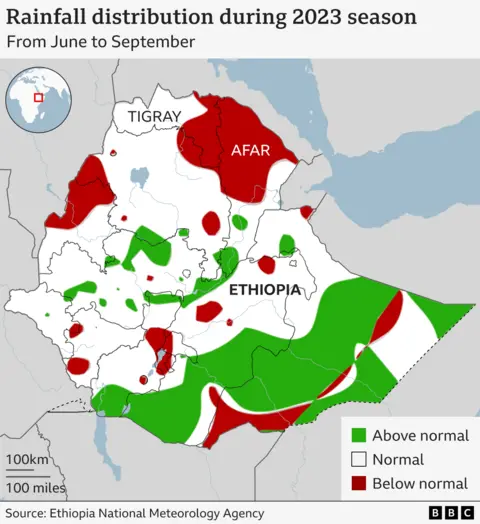

Data obtained from the Meteorology Center of the Ethiopian government shows the result of poor rains last year.

The northern regions of Tigray and neighboring Afar are both affected by drought.

In southern Ethiopia, heavy rains caused floods, damaging crops and livestock.

Rainfall in January and February this year was also below normal in large parts of Tigray, although it improved elsewhere in March.

Political differences

Hunger “rises in the dark” warns Prof. Alex de Waal, executive director of the advocacy group, the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University. He says very little attention is paid to this problem.

“Famine is created by people, so the men who do it like to hide the evidence and hide their role,” he said.

He says the current situation in Tigray is similar to the famine crisis of 1984 in which about a million people died due to hunger.

“In 1984, the Ethiopian government wanted the world to believe that its revolution heralded a bright new era of prosperity, and foreign donors refused to believe the famine warnings until they saw pictures of dying children on the BBC news.”

Aid agencies have mapped the scale of the crisis facing Ethiopia based on a number of factors, including the failure of rainfall, ongoing insecurity and lack of access to aid distribution.

The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (Fews Net) describes parts of Tigray, as well as neighboring Afar and Amhara, as facing an emergency.

Getty/Ed Ram

Getty/Ed RamThe federal government in Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, opposes these food shortage warnings.

Shiferaw Teklemariam, head of Ethiopia’s National Disaster Risk Management Commission, told the BBC that based on official assessments “there are no future risks of famine and famine in Tigray…[or] somewhere in Ethiopia.”

He added that officials are “doing everything they can” to address the challenges facing the country and that “the most needy beneficiaries” will continue to be prioritized.

Relations between the Ethiopian government and aid agencies have been strained in recent years, amid allegations by the UN that food aid was being blocked from reaching Tigray during the conflict there.

In 2021, the federal government denied reports of famine in Tigray and fired seven UN staff, accusing them of “interfering in the country’s internal affairs”.

In June last year, the World Food Program and the US Agency for International Development (USAID) stopped all food aid to Ethiopia, saying they had uncovered evidence that government and military officials were stealing aid supplies.

Delivery only resumed in November.

There have been arguments in the public and in Ethiopia about the seriousness of the situation.

In February, after Ethiopia’s coroner reported that nearly 400 people had died of starvation in the country, including in Tigray, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said: “There are no people dying of starvation in Ethiopia.”

Responding to this political tension, Alex de Waal says that aid organizations that are “strapped for funding and conflict-ridden” have been slow to respond to the current crisis.

A USAID spokesperson told the BBC that they “continue to urge the government of Ethiopia and other donors to increase humanitarian funding for the most vulnerable”.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) says that current funding is “insufficient to meet most humanitarian needs”, but available resources are being channeled to “urgent, life-saving responses.”

Additional reporting by Daniel Palumbo and Kumar Malhotra

Source link