Caddying is now a profession. This one started a training program

Professional tour caddies play important roles and are paid accordingly.

Getty Images

About 50 years ago, long before he worked for the likes of Curtis Strange, Greg Norman and Payne Stewart, Mike Hicks got his first job as a pastor, serving as a local pastor at a club in his hometown of North Carolina. Hicks was 12 years old. His salary was $5 per loop.

In those days, caddying was considered a viable occupation. Without exception, it was considered a shortcut for those with no better options, or a summer gig for the Danny Noonans of the world. Hicks didn’t see it as a way to make a living.

He says: “I have never been happy with this idea.

In 1980, however, as an undergraduate at North Carolina State, Hicks was considering taking a semester off when a friend who was coaching Tour pro JC Snead encouraged him to join him in California and ride the West Coast swing.

“He said, ‘You can work for the pro-am, as well as those who qualified for Monday. You’ll get through,’” Hicks said.

Hicks went home with $140 and came back eight weeks later with a big bang and doubled his money. He was 19 years old. There was no looking back.

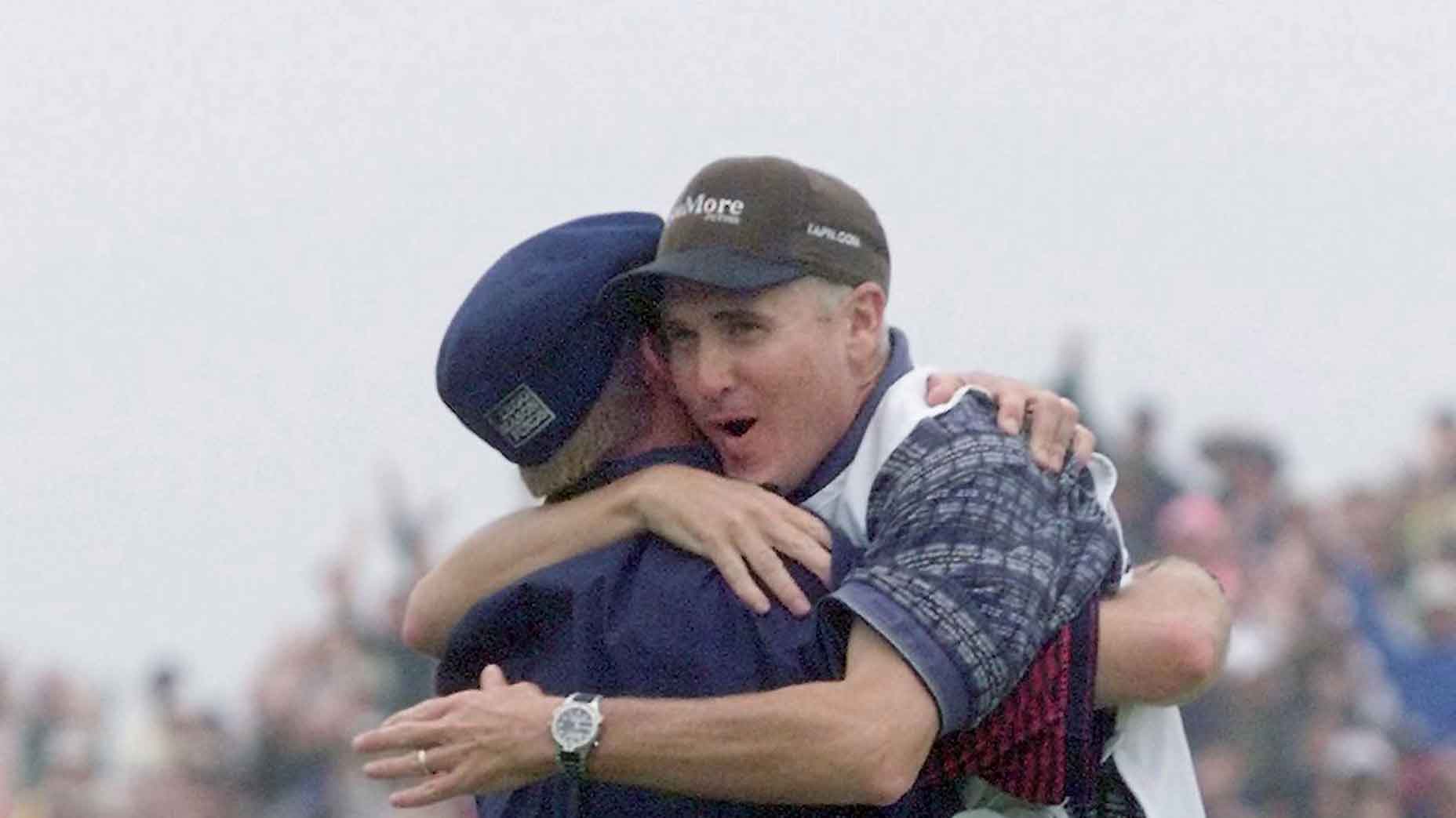

For Hicks, it was the start of many years as a respected Tour looper (a photo of Hicks jumping into Stewart’s arms after his boss won the ’99 US Open is part of the match photo). He is 63 years old now, he just retired from the circuit. And the trade he was doing has been completely changed.

Getty Images

Caddying these days does more than pay bills. In high-end clubs and resorts, loops usually lead six people. Top Tour professional caddies are worth millions. The work was done professionally. What is often missing, however, is formal formal training.

That’s something Hicks is trying to change.

A founding member of the Tour Caddy Collective, a network dedicated to developing the next generation of caddies, Hicks partnered with fellow Tour loopers Grant Berry and Heath Holt to launch the Professional Caddy Certification Program. This program, run in collaboration with the Office of Professional Development of North Carolina State University, aims to provide 18 participants with seven days and one night of intensive education covering all aspects of the profession. The opening session begins on December 1.

“We’ll be getting into all the nuances,” Hicks said.

In cliche construction, caddying has three basic requirements: Show up, keep quiet and shut up.

That doesn’t work anymore.

First, Hicks says, “It’s the opposite of ‘shut up.’ At the highest levels, however, most players expect open communication, a point that is emphasized every time the TV networks listen to Michael Greller and Jordan Spieth. From one partnership to another, and from one shot to the next, the caddy’s role can change from sidekick to psychologist to security guard, and beyond. Quantitative skills are increasingly needed. So is emotional intelligence.

“A player-caddy relationship is like a marriage,” says Hicks. “But you also have to be a mathematician. You don’t just add and subtract. You are dealing with percentages. He analyzes statistics and uses live data to help the boys with course management.”

To help participants prepare for those varied demands, Hicks says the program will be taught by multiple instructors, including a sports psychologist, a physiotherapist, a PGA Tour official and technical experts such as Trackman, Aimpoint and GC Quad.

There will be a class on CPR.

“He told me how many caddies out there know CPR,” Hicks said. “Not really, I’ll tell you that.”

Even as they take care of their players, Hicks says, caddies need to learn to take care of themselves.

“Stretching is an important part of caddying,” Hicks said. “You have to eat well, and get enough rest.”

In those limitations, Hicks admits, he failed in his mission.

He says: “It’s really a miracle that I’m still here.”

But time is a great teacher, and now he has the opportunity to share what he has learned with others. Although the plan is to make the plan permanent, the long-term plan has not been set. The second session is scheduled for February. But the first session in December, Hicks says, is a “pilot” that he expects will change over time. Cost is $4,000 per participant.

“We want to fix it,” he said. “And we’ll see where it leads.”

For more information, go.ncsu.edu/golf-caddie-cert or contact info@tourcaddiecollective.com.

Source link