The regime of the rebels in Idlib indicates what else Syria can expect

Reuters

ReutersThe road to Idlib, in the far northwest corner of Syria, still bears the marks of the old front lines: trenches, abandoned military positions, rocket shells and ammunition.

Until a little over a week ago, this was the only place in the country controlled by the opposition.

From Idlib, rebels led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, launched a stunning offensive that toppled Bashar al-Assad and ended his family’s five-decade dictatorship in Syria.

As a result, they have become the authorities of the country and seem to be trying to bring their style of administration to the whole of Syria.

In the center of the city of Idlib, opposition flags, with a green stripe and three red stars, are flying high in the squares and are being waved by men and women, old and young, after the removal of Assad. The paintings on the walls celebrated resistance to the regime.

While destroyed buildings and piles of rubble were reminders of a war not so far away, renovated houses, newly opened shops and well-maintained roads were proof that some things had indeed improved. But there were complaints about what was seen as harsh treatment by the authorities.

When we visited earlier this week, the roads were relatively clean, the traffic lights and bollards were working, and the police were present in the busiest areas. Simple things do not exist in other parts of Syria, and a source of pride here.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCHTS has its roots in al-Qaeda but, in recent years, it has tried to reinvent itself as a nationalist force, far removed from its jihadist past and aiming to oust Assad.

As fighters marched on Damascus earlier this month, its leaders spoke of building Syria for all Syrians. However, it is still classified as a terrorist organization by the US, UK, UN and others, including Turkey, which support the Syrian rebels.

The group took control of most of the region, home to 4.5 million people, in 2017, bringing stability after years of civil war.

The administration, known as the Salvation Government, is in charge of water and electricity distribution, garbage collection and road traffic.

Taxes collected from businesses, farmers and the Turkish border finance its public services – as well as its military operations.

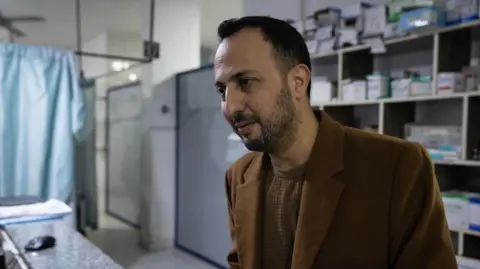

“Under Assad, they used to say that Idlib was a forgotten city,” said Dr. Hamza Almoraweh, a cardiologist, while treating patients at a hospital housed in a postal warehouse.

He left Aleppo with his wife in 2015 when the war intensified, but he had no plans to return, even though the city was under the control of the rebels.

“We’ve seen a lot of progress here. Idlib has a lot of things that it didn’t have under the Assad regime.”

As it moderated its tone, seeking international recognition amid local opposition, HTS withdrew some of the strict social laws it had imposed when it came to power, including dress codes for women and music bans in schools.

And some people cite recent protests, including government-imposed taxes, as evidence that some level of criticism is being tolerated, as opposed to Assad’s repression.

“It is not a full democracy, but there is freedom,” said Fuad Sayedissa, an activist.

“There were problems in the beginning but, over the years, they have been working in a better way and are trying to change.”

Originally from Idlib, Sayedissa now lives in Turkey, where she runs the non-governmental organization Violet. Like thousands of Syrians, the fall of Assad meant he could visit his city again – in his case, for the first time in ten years.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCBut there have also been protests against what some say is a dictatorship. Combining power, experts say, this group targeted extremists, arrested opponents and arrested their opponents.

“How the government will act in the rest of Syria is a different story,” Sayedissa said. Syria is a diverse country and after decades of repression and violence by the regime and its allies, many are standing for justice. “People are still celebrating, but they’re also worried about the future.”

We tried to talk to a local official, but we were told that they had all gone to Damascus to help the new government.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCAn hour’s drive from Idlib, in the small Christian village of Quniyah, church bells rang for the first time in a decade on December 8 to celebrate Assad’s removal.

The community, near the Turkish border, was bombed during the civil war, which began in 2011 when Assad crushed peaceful protests against him and most of its residents fled.

Only 250 people remained.

“Syria is better now that Assad has fallen,” said Friar Fadi Azar.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCThe rise of Islam, however, has raised fears that minorities, including Assad’s Alawites, may be at risk, despite messages from HTS assuring religious and ethnic groups that they will be protected.

“Two years ago, they [HTS] he started to change… Before, it was very difficult,” said Friar Azar.

Goods were confiscated and religious practices were banned.

“They gave up [our community] more freedom, they ask other refugees Christians to come back and take their lands and their homes.”

But is this change real? Can they be trusted? “What can we do? We have no other choice,” he said. “We trust them.”

I asked Sayedissa, an activist, why even her opponents were reluctant to criticize the party.

“Now they are heroes… [But] we have red lines. We will no longer allow dictators, Jolani or anyone else,” he said, referring to Ahmed al-Shara, the HTS leader who changed his name to Abu Mohammad al-Jolani after taking office.

“If they act like a dictator, people are ready to reject, because now they have freedom.”

Source link