‘I make my own burial cloth to avoid defilement’

Lizzy Steel / BBC

Lizzy Steel / BBC“I don’t want my last act on this planet to be a polluting act, if I can help it,” explained Rachel Hawthorn.

He is preparing to make a burial cloth for himself because he is concerned about the environmental impact of human burial and cremation.

“I try hard in my life to recycle and use less, and to live in an environmentally friendly way, so I want my death to be like that,” he adds.

Cremation produces the same amount of carbon dioxide emissions as a return flight from London to Paris and around 80 per cent of those who die in the UK are cremated each year, according to the report. report from the carbon consultancy company, Planet Mark.

But traditional burials can also pollute. Non-biodegradable coffins are often made from harmful chemicals and bodies are embalmed using formaldehyde: a toxic substance that can leach into the soil.

Lizzy Steel / BBC

Lizzy Steel / BBCIn a recent survey from Co-op Funeralcare, run by YouGov, 1 in 10 people said they would want an ‘eco-friendly’ funeral.

Rachel, from Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire, made a burial shroud for her friend from locally sourced wool, willow, bramble and ivy, as part of her craft.

For years he has been exploring the themes of death, dying, grief and nature using art and practical materials.

But the 50-year-old sees the canvas, which can eliminate the need for a box, as more than just paintings – and has decided to make his own.

A common reaction of those who have seen the creation is to ask if they can touch it, to feel how soft it is.

For Rachel, it’s the perfect way to help people deal with the taboo topic of death.

She also works as a bereavement doula, which involves supporting dying people, and their loved ones, to make informed funeral care decisions.

“I find that when we talk about death, everyone I’ve met has found it helpful and healthy, and something that enriches life,” he said.

“When someone dies, it’s often very scary. We just get on the ‘this is what’s happening’ treadmill, so I want to open up those conversations.

“I want more people to know that there are options and that we don’t have to end up in a box.”

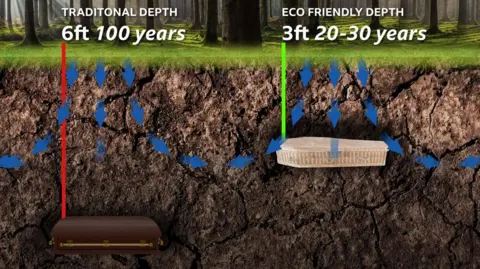

The practice of digging graves to a depth of 6 meters (1.82m) dates back to at least the 16th Century and is believed to have been a warning against plague.

When Rachel’s time comes, she wants a natural burial, which means using a decomposing coffin or being buried in a shallow grave. The top layers of soil contain active bacteria, so bodies can decompose in 20 to 30 years, rather than 100 in a traditional grave.

Natural burial grounds are dotted all over the UK and are very different from traditional cemeteries – trees and wildflowers replace man-made grave markers, and no pesticides are used.

Embalming, headstones, ornaments, and plastic flowers are prohibited.

Louise McManus’ mother was buried last year at Tarn Moor Memorial Woodland, a nature reserve near Skipton. The funeral included an electric hearse, a locally made wool casket and flowers from her garden.

“He loved nature and being outdoors. He was concerned about what was happening to the environment and asked for his funeral to be as sustainable as possible,” said Louise.

Sarah Jones, a Leeds-based funeral director who organized the deployment, says the need for sustainability is growing.

His business has grown to four locations since opening in 2016 as the growth of sustainable funerals has helped fuel that expansion.

He said at “a few” eco funerals, such requests now make up about 20% of his business.

“More and more people are asking about it and want to make decisions that are good for the planet. Most of the time, they think it shows the life of a deceased person because it was important to them,” he said.

Lizzy Steel / BBC

Lizzy Steel / BBCLike many environmentally friendly industries, landfilling can be expensive. Many grounds, including Tarn Moor, offer cheap pitches to locals. One in Speeton, North Yorkshire, is run by the community and returns profits to a rural play area.

At Tarn Moor, the site and repairs cost the residents of Skipton £1,177. Non-locals are charged £1,818. A nearby council cemetery charges £1,200 for a grave while cremation costs here start at £896.

Often away from urban areas and transport links, going to natural burial sites, or visiting a cemetery, can involve a higher carbon footprint than more traditional sites, says the Planet Mark report.

Textile maker Rachel recognizes these challenges but hopes for long-term change. He wants to see more local environmental causes and make environmentally friendly death care the norm, while respecting the choices of others.

“In the past, women would come to their matrimonial home with their cloth as part of the dowry and they would be kept in the bottom drawer until they were needed,” he said.

“I don’t see why people can’t prepare their burial cloth and wait for them.

“I think that would be normal, but everyone needs to make their own choices. It doesn’t have to be a certain way.”

Source link