Cop29: US out, China in

BBC

BBCThe WhatsApp message was from the chief negotiator of one of the most powerful countries at the COP climate meeting. Can I stop by so we can talk, he asked.

As his team hunted for computers and ate takeaway pizza, he became angry at the restrictive behavior of many of the other teams at the conference.

So far, so normal. Others have been saying versions of this all week – that this was the worst COP ever; that the negotiating documents, intended to be slimmed down as the deadlines approached, actually ballooned; that the COP in its current form may be dead in the water…

What was watching over all was the hope that the president-elect of the US, Donald Trump, would withdraw the US from the COP program when he takes office for the second time. He called climate action a “scam” and, at his victory celebration in West Palm Beach earlier this month, vowed to boost US oil production beyond current levels, saying, “We have more liquid gold than any country in the world”.

But there was one good one: China.

“It’s the only bright spot in all of this,” a senior spokesman told me. Not only was its negotiating style markedly different from previous years, but he also noted that, as he put it, “China may move forward.”

So what would it mean for the global effort to deal with climate change if you get ahead, just as the US backs off?

Negotiation styles – a change of tack

In the past, China has played a dual role in these negotiations. Sometimes it aligns with the US and Europe, for example in targeting ambitions to develop renewable energy or in the reduction of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. In other matters, on the other hand, it has slowed progress.

One such example was COP15, which was held in Copenhagen in 2009. There were high hopes that an agreement would be reached to commit countries to significantly reducing carbon emissions. But the summit nearly collapsed when China resisted US pressure to submit to the international surveillance regime. The final non-binding agreement was generally considered a failure.

This year was different. A senior negotiator I spoke to said that China has been “extraordinarily cooperative” in all negotiations.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe most obvious sign of this came at the start of the conference, when China made public information about its climate funding.

Traditionally, China has released little information about its climate policies and programs, so it came as a surprise when, for the first time, officials said it had paid developing countries more than $24 billion for climate action since 2016.

“That’s serious money, probably nobody else is at that level,” one COP insider told me.

This made the conference silent. “It is a significant sign,” said Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub, “as it is the first time that the Chinese government has put a clear figure on how much money it has been providing.”

Developing country vs superpower

China is classified as a developing country according to the UN climate talks, despite being the second largest economy in the world, the result of an exception to the rules of the COP. (This is linked to its economic situation in 1992 when the negotiation process began.)

It has long resisted pressure from developed countries to change its stance, meaning that it should not contribute to the pot that rich countries have agreed to pay for the poor.

That pot was one of the main focuses of the speech in Baku. It’s up to $100 billion a year now, but developing countries — those with low and middle income — need at least another billion dollars a year to help them transition to clean energy and deal with the effects of climate change, according to the World Economic Forum.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat kind of subsidy it takes is another question, since little data is available. What is known is that Chinese money is helping to fund projects such as solar farms and energy-saving lights in some developing countries such as Rwanda, where electric buses made in China have been used in the capital Kigali.

“What is so interesting is the language used by the Chinese,” said Professor Michael Jacobs, an expert in climate politics at Sheffield University. “They described it as ‘provided and integrated’ – that’s the term developed countries use for their payments.”

Language issues at climate conferences. Negotiators can spend days discussing whether something “should” or “will happen”. Therefore, the Chinese echoing the language of a rich country is important, said Prof Jacobs.

“They used to measure everything against what the US was doing,” he says. When Trump took office in 2016, China stepped up negotiations in response. This time is different, according to Prof. Jacobs.

“This looks to me like a request for leadership.”

What is there in Mpumalanga?

“It’s not like that [driven by] to consider the Chinese side,” continued Professor Jacobs.

According to Li Shuo, the changing economy of renewables explains why China is likely to move forward.

The green revolution is largely led by China – not the government, but its private sector and corporations”. These companies lead the world by what Shuo calls “the most significant margin”.

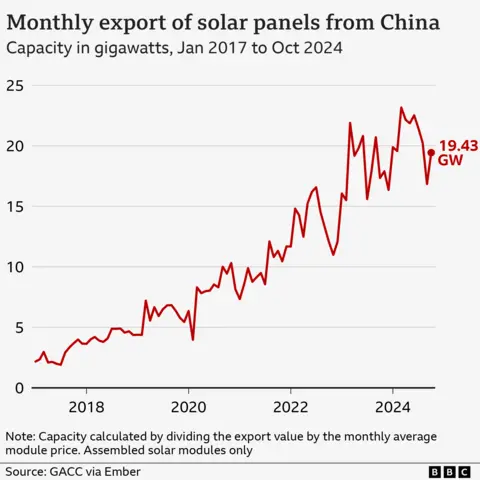

Eight out of ten solar panels are made in China, and they account for two-thirds of wind turbine production. It is considered to produce at least three quarters of the world’s lithium batteries and more than 60% of the global market for electric vehicles.

Earlier this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping said solar panels, EVs and batteries are the “three new things” at the heart of China’s economy.

The huge investment China has made in renewable technology and the huge economies of scale it has created have driven down the cost of renewables year after year – the challenge it now faces is finding new markets to sell to.

In developing countries this is where the demand will grow. These countries will account for two-thirds of the renewable market within 10 years, according to a recent report by an economic group commissioned by the UN to calculate the cost of energy transition.

Pakistan imported 13 gigawatts (GW) of solar panels in the first six months of this year alone, according to a study by Bloomberg NEF. To put that in context, the UK has 17GW of solar installed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesExporting clean technology to developing countries is in line with one of China’s policies: the “Belt and Road Initiative,” an effort to develop new trade routes, including roads, railways, ports and airports, to connect with the rest of the world.

China has spent more than a billion dollars on the project, according to the World Economic Forum. Last week, President Xi opened a new port on the coast of Peru.

The first to explain why, as Prof Jacobs sees it, while the US may be withdrawing, China looks like it may be on the rise. “Now it sees its best interest as encouraging other countries to reduce their emissions by using Chinese technology and equipment.”

A tectonic shift in climate discourse

If China takes a more prominent role, it will mark a tectonic shift in the COP process. Historically, the West – especially the US and the EU – have provided the impetus, which has been enjoyed by smaller climate-vulnerable countries. The difference in how conversations play out will be noticeable.

Jonathan Pershing, director of the environmental program at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, has been to every COP and has a better understanding of the behind-the-scenes trade-offs, bullying and subterfuge that make or break deals at conferences. He says that China will not lead the way, like the US and Europe.

“They are more cautious players than that. They may be leading the way in Chinese characteristics, which are things they can’t say themselves.”

(This echoes how Deng Xiaoping, president in the early 1980s, described his economic reforms, which led to the country’s economic growth in the double digits: “residence with Chinese characteristics”.)

Pershing suggests that China may help move the COP process forward by strategically intervening to open up the conflict. Most of these efforts will take place behind closed doors, he believes, but they are likely to involve urging developing and developed countries to increase their ambitions – and the flow of money.

However, China may not be entirely helpful in other challenges that delay the process, such as situations where countries use the COP as a forum to fight for their interests.

One of the main obstacles in Baku is said to be Saudi Arabia, which leads a group of oil-producing countries that want to slow the transition to renewables. As a major consumer of fossil fuels, China has often thrown its weight behind it in the past, such as resisting the UK’s attempt to secure a deal to phase out coal at COP26 in Glasgow.

However, there is finally reason for optimism, according to some well-placed observers. Camilla Born, who was part of the UK negotiating team and helped run COP26 in Glasgow, believes future negotiations will be determined by a new energy economy, not convention politics.

“This is not just an idea of how to deal with climate change,” he said. “This is about investment, money – it’s people’s jobs, it’s new technology. Conversations are different.”

After all, it is the biggest energy revolution since the industrial revolution began. And regardless of which superpower leads, or if the US is out of the game for four years, it’s unlikely that anyone would want to miss out on such a huge market.

BBC InDepth is the new home to the website and app for analysis and the best information from our top journalists. Under a brand new brand, we’ll bring you fresh ideas that challenge assumptions, and in-depth reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sound and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking the button below.

Source link